아침놀 Blog

Daybreakin Things

9 Entries : Results for In English/Learn Korea

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

It was exactly 39 days ago when I left Sweden. I've been busy for many things, such as interviews for software engineer internship of Google Korea1, and also Textcube 2.0 designing and prototyping.

Well, just after I came back to Korea, I found a very good website that provides Korean-learning materials. Here is the link. :P It has several subscription options including both free and paid. I think the free one should be sufficient to learn basic Korean.

Instead of introducing details of Korean language, I'm going to tell about my normal life and Korean culture in many aspects, for example, favorite websites used by Korean people, famous vacation places, and traditional foods.

I'm not sure that I could keep writing bilingual posts here, but I'm planning to add a function which enables multi-lingual posts for Textcube 2.0. Then, I will be able to provide more convenient reading to foreign visitors.

-

Yes, I just finished the second team interview last Monday. Now I'm waiting for the result. ↩

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

As I said in the first introduction, the best way to learn exact pronunciation is making a Korean friend, or listen to pronunciations of native speakers. Although, I want to show you as possible.

You may have seen a famous American TV series 'Lost'. There appear a Korean actor and an actress. The actor Daniel Dae Kim is not an actual native speaker though he was born in South Korea because he immigrated to United States at two years old. So that's why his pronunciation looks weird and funny for native speakers. (Some people even say it's addictive.) -_-; But the actress Yunjin Kim's pronunciation is more native.

Romanization of Korean

There are several methods to express Korean pronunciations using Latin characters. The current standardized system is Revised Romanization of Korean, also called 'RR'. Formerly used one is McCune-Reischauer method. But neither two methods are completely reflecting actual Korean. Anyway what I used here to express pronunciations is RR method.

Rules to make it fluent

The Korean character system, "Hangul", represents the sounds of Korean. But not to make it confusing, another main principle to write Korean is to keep the original forms of words.

Thus, sometimes spoken Korean differs from written Korean. There are some rules to convert written Korean to spoken Korean as a standard. Here is an article about this topic. (The romanization used in this article is not RR, but IPA.) Though it's explaining in Korean, but I think you may be able to see what kinds of differences exist if you know the components of Hangul.

- Tag Korean, lecture, pronunciation, 발음, 한국어

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

This article explains how to use Korean dictionaries to find out the meaning of new words you meet.

How to type Korean in your computer?

I think most of you, epsecially Western people, would have difficulties to get a Korean dictionary book with your native languages or English here. So I recommend you to use some free web dictionaries.

Before that, you should be able to input Korean characters on your computer. I found a good guide to do this.

For MacOSX, you can just activate Korean Input Method in the international panel of the system preferences dialog. You can also see character palettes to see which key is mapped which Hangul jamo.

Using free Kor-Eng/Eng-Kor web dictionaries

Now you can use Korean-English dictionaries on the web. I recommend you to use Naver English Dictionary. It's all Korean, but you should be able to find the input box in the main screen. You may type both Korean or English words to translate into each other.

You would see something similar to this if you have correctly installed Korean fonts.

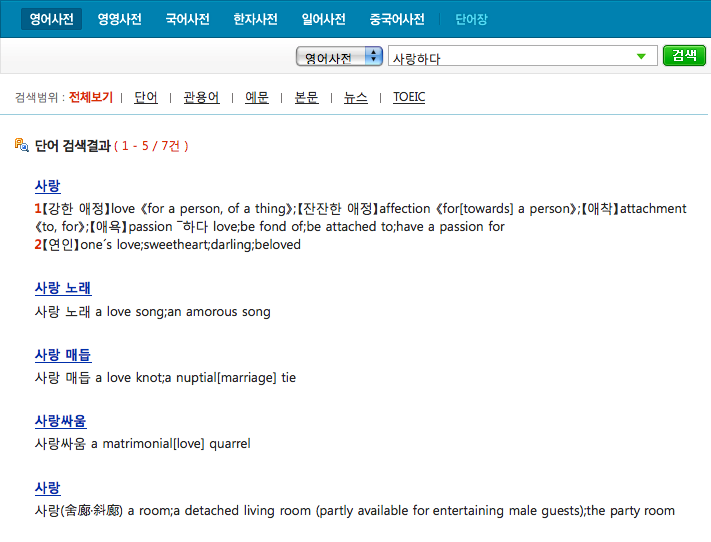

For verbs and adjectives, you should use a default(dictionary) form, for example, '-하다'. I will explain the variation of Korean verbs soon.

An example of using it. If that word have multiple meanings or uses, then it shows a list of entries.

You may also try English words like this. For Chinese and Japanese people, Naver also provides Chinese/Japanese dictionary. Though these dictionaries are designed for Korean, but it might be more helpful for you than English ones.

- Tag dictionary, Hangul, Korean, korean ime, lecture, 영어사전

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

Now, it's time to begin some grammar-related things. I think the most easiest part to learn in languages is nouns, so this post is about Korean nouns.

Basic Vocabulary

To make it more interesting, you need to know some basic vocabularies.

| English | Korean | Desc. |

|---|---|---|

| name | 이름 | |

| man | 남자(男子) | |

| woman | 여자(女子) | |

| child(ren) | 어린이 | |

| water | 물 | |

| food | 음식(飮食) | |

| human, people, person | 사람, 인간(人間) | |

| human race, mankind | 인류(人類) | |

| earth | 땅, 지구(地球) | '땅' is used being compared to the sky, and '지구' means our planet. |

| sky | 하늘 | |

| tree | 나무 | |

| sea | 바다 | |

| land | 땅 | |

| house, home | 집 | |

| building | 건물(建物) | |

| road, pathway | 길 | |

| school | 학교(學校) | |

| university, college | 대학교(大學校) | |

| student | 학생(學生 ) | |

| language | 말, 언어(言語) | |

| sun | 해, 태양(太陽) | |

| moon | 달 |

I will show family names in the following lecture.

Same Pronunciation with Different Meanings

Because Korean has much more simplified pronunciations than Chinese has, there are many words that have different meanings but same pronunciations. In fact, sometimes there are differences on the length of vowels which are usually ignored by Koreans. Koreans determine the meanings depending on the context.

| Korean | English |

|---|---|

| 차(茶) | tea |

| 차(車) | car, vehicle |

| 눈 | eye |

| 눈ː1 | snow |

| 말 | horse |

| 말ː | words, speaking, language |

| 배 | ship |

| 배 | pear |

| 배 | the abdomen |

| 배(倍) | doubles/multiples of something |

| 감(感) | feeling, thought |

| 감 | Japanese persimmon |

| 사과(沙果/砂果) | apple |

| 사과(謝過) | making an apologize |

Nouns from Foreign(Latin) Languages

We approximate2 the pronunciations of words from English, French, and other languages. Sometimes those approximation are different between North Korea and South Korea because dialects of North Korea have stronger consonants and heavily affected by Russia. Here, I will use only South Korean.

| English | Korean |

|---|---|

| computer | 컴퓨터 |

| program | 프로그램 |

| project | 프로젝트 |

| bus | 버스 |

| taxi | 택시 |

| hotel | 호텔 |

| casino | 카지노 |

| spaghetti | 스파게티 |

| pasta | 파스타 |

| cake | 케이크 |

| ice cream | 아이스크림 |

| show | 쇼 |

| sofa | 소파 |

| television | 텔레비전 |

| coffee | 커피 |

Some words are transformed under influence by Japanese, or just "Konglish" (Korean English).

| English | Korean |

|---|---|

| air conditioner | 에어컨 |

| remote controller | 리모콘 |

| cell phone | 핸드폰 -- came from 'hand phone' which is not standard English; many people insist that we should use a better expression, '휴대전화(携帶電話)'. |

And of course, the names of many countries and regions in the world are in this category.

| English | Korean |

|---|---|

| Asia | 아시아 |

| America | 아메리카 |

| Europe | 유럽 |

| Sweden | 스웨덴 |

| Russia | 러시아 |

| Canada | 캐나다 |

| Mexico | 멕시코 |

| Finland | 핀란드 |

| France | 프랑스 |

| Spain | 스페인 |

| Italy | 이탈리아 |

| Egypt | 이집트 |

| Taiwan | 타이완 |

| Arab | 아랍 |

| Dubai | 두바이 |

| Beijing | 베이징 |

| Stockholm | 스톡홀름 |

| Hongkong | 홍콩 |

| Tokyo | 도쿄 |

| Amazon | 아마존 |

| Washington | 워싱턴 |

| Berlin | 베를린 |

and many others.

But the names of some countries which were introduced by Japan or in earlier periods are used in Hanja representations.

| English | Korean |

|---|---|

| Republic of Korea | 대한민국(大韓民國) -- The official name of South Korea. Usually an abbreviation '한국(韓國)' is used. |

| South Korea | 남한(南韓) |

| North Korea | 북한(北韓) |

| United States | 미국(美國) -- Japan use 米國. |

| Great Britain (United Kingdoms) | 영국(英國) -- 'English' is '영어(英語)'. |

| Japan | 일본(日本) |

| China | 중국(中國) |

| German | 독일(獨逸) |

| France | 불란서(佛蘭西) -- Obsolete word now, but the character '佛' is still used in newspapers as an abbreviation. |

The name of our country, "Korea", is made from the name a kingdom which existed at the medieval age in the Korean peninsula, "고려(高麗)". This kingdom had very activated trades of many products with other countries including China and Arabs.

Subjective & Objective Form and Pronouns

Basically, we don't distinguish subjective and objective forms because we have postpositions that indicates the role of the words which it decorates. I will introduce postpositions later.

| English | Korean |

|---|---|

| I, me | 나, 저 -- The later one is an honorific form that lowers the speaker compared to the listener. |

| You | 너, 자네, 당신3 |

| We | 우리 |

| He | 그 |

| She | 그녀 |

| They | 그들 -- same to the plural form of '그' |

| This | 이것 |

| That | 저것 |

| It | 그것 |

To make them adjectives, like 'my', 'your', 'his', and etc, you can just append a postposition '~의'. Exceptionally 'my' and 'your' can be also used as '내/제' and '네' respectively. To represent someone's belongings, just append another word '것' which means (some)thing, like 'mine' = '나의 것/내 것/제 것', 'yours' = '너의 것/네 것', and 'his' = '그의', '그의 것'.

Single and Plural

To make nouns plural, you may just append a suffix '들' like '-s' or '-es' in English. There is no variation of original nouns. But Korean language does not strictly distinguish single and plural nouns, so this can be omitted in many cases. Usually if a noun is decorated by adjectives or used as a subject, then the plural form is more frequently used.

Articles

Korean does not have articles such as 'a', 'an', and 'the' in English. You can just put nouns in proper positions without any articles and any pluralization. If you want to emphasize that a noun is single, you may use '한'(the attributive form of ordinal number/native cardinal one) in front of it, but this is not necessary and actually unnatural in many contexts.

There is no strict separation between uncountable and countable nouns. They are countable or uncountable only conceptually, with no grammatical differences due to absence of articles. Of course, we don't pluralize uncountable nouns such as '사랑' which means 'love'.

In fact, putting proper articles for various abstract nouns is the most difficult part for Koreans when they learn English. (Maybe this post has also many mistakes about this.)

-

The symbol 'ː' means the vowel of the character just before it should be pronounced long, but rarely distinguished by Korean people. ↩

-

This is called 'transliteration' formally. ↩

-

In subjective form with some postpositions, this should be used as '네', but many Korean does not care of it. ↩

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

Basically Korean uses the same system of Western society (Gregorian calendar) to represent dates and times. The standard time zone of South Korea is GMT+09:00 without the summer time period. It's same to Tokyo, Japan.

For traditional holidays, we count them on a lunar calendar which is based on Chinese calendar. We don't have any traditional holidays based on weekdays like United States (eg. Thanksgiving day is the fourth Thursday of November in U.S.) because we didn't have the weekday concept before Western culture was introduced.

We had a very different calendar system at the past, which divided a year into 24 periods and count the year based on the starting years of kings' ruling period1 or 60 years of "Kanji" cycles. Before using the concept of weeks, China and Korea usually divided a month into 5 or 10 days. I will introduce this traditional calendar system on another post later.

Weekdays

| English | Korean | Hanja2 | Desc. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Monday | 월요일 | 月曜日 | 月 = moon, month |

| Tuesday | 화요일 | 火曜日 | 火 = fire |

| Wednesday | 수요일 | 水曜日 | 水 = water |

| Thursday | 목요일 | 木曜日 | 木 = tree, wood |

| Friday | 금요일 | 金曜日 | 金 = metal |

| Saturday | 토요일 | 土曜日 | 土 = soil |

| Sunday | 일요일 | 日曜日 | 日 = sun, day |

You may notice the name of monday and sunday have the same meaning to English ones. Also other names have some relations to English names.3 For example, saturday is come from 'Saturn' which also means the sixth planet of our solar system and we say that planet as '토성(土星)'. These weekdays names are influenced by Japan that uses same names.4

5-days work on a week is now widely accepted in South Korea, so the friday is beginning of weekends like most Western countries, but without shortened work time at that day. (In Sweden, the work time on fridays is often shorter than other weekdays, but in Korea, there is almost no exceptions.)

Saying Years, Months and Days

We write dates in 'Year Month Day' order while Americans use 'Month Day Year' and Sweden uses 'Day Month Year'. Almost everybody knows English month names though they are not used frequently in Korea, and there are no month names in (modern) Korean.5

So we just say January as '1월', February as '2월', ..., December as '12월'. The character '월' is Korean pronunciation of Chinese character '月' which means month or the moon. All numbers in dates are said in the cardinal number form.

Generally, year is '년(年)', month is '월(月)', and day is '일(日)' or '날'6.

Example: April 12, 2008 = 2008년 4월 12일 (이천팔년 사월 십이일)

Usually 3000BC is said '기원전(紀元前) 3000년' and AD2000 (or CE2000) is said '기원후(紀元後) 2000년' in some historical contexts. '기원' means a specific moment of a historic event depending on the context--here, the birth of Jesus Christ.

Saying Time

To say hours in Korean, you should use ordinal numbers, but cardinal numbers for minutes and seconds.

I think it would be faster to look some examples.

| English | Korean | Hanja |

|---|---|---|

| AM | 오전 | 午前 |

| PM | 오후 | 午後 |

| hour | 시 | 時 |

| minute | 분 | 分 |

| second | 초 | 秒 |

| 1:00AM | 오전 1시 [오전 한시] | |

| 2:00PM | 오후 2시 [오후 두시] | |

| 5:30 | 5시 30분 [다섯시 삼십분], 다섯시 반(半) | |

| 11:50 (ten to twelve) | 12시 10분 전(前) [열두시 십분 전] |

We don't have some varied expressions to say times such as 'ten past twelve', 'a quarter past three', etc in English, but just say the exact numbers.

General Nouns about Times

| English | Korean |

|---|---|

| noon | 한낮, 정오(正午) |

| morning | 아침 |

| afternoon | 오후(午後) |

| evening | 저녁 |

| night | 밤 |

| day(time) | 낮 |

Time Span

We use '시간(時間)' instead of '시(時)' and other parts are same.7

| English | Korean |

|---|---|

| 10 hours | 10시간 [열시간] |

| 2 hours 7 minutes 3 seconds | 2시간 7분 3초 [두시간 칠분 삼초] |

-

This is often called Regnal year. ↩

-

From now, I will use this expression instead of 'Chinese characters' because 'Hanja' has another meaning that those characters are borrowed and incorporated to Korean language so that there might be some differences to the original Chinese. See this. ↩

-

Read this. (Korean) ↩

-

During the Japanese occupation period (1910-1945), many words from Western culture were brought by Japan. So many of current Korean nouns are same to Japanese nouns, but often different from Chinese. ↩

-

In traditional calendar, we also have names for each month, but currently they are almost not used. ↩

-

'일' is used as a unit of time while '날' as a general conceptual noun. ↩

-

We do not use plurals here. I didn't introduce plurals in Korean yet, but actually plurals are much less used than English. ↩

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

Using numbers in Korean is very similar to Japanese and Chinese because those three use same Chinese numbers with different pronunciations. But this fact is applied for only cardinal numbers(one, two, three, ...), not ordinal numbers (eg. first, second, third, ...).

Basic Reading

| Arabic | Cardinal | Ordinal prototype1 | Chinese cardinal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 일[il] | 하나[hana] | ⼀ |

| 2 | 이[i] | 둘[dool] | ⼆ |

| 3 | 삼[sam] | 셋[set] | 三 |

| 4 | 사[sa] | 넷[net] | 四 |

| 5 | 오[o] | 다섯[daseot] | 五 |

| 6 | 육[yuk] | 여섯[yeoseot] | 六 |

| 7 | 칠[chil] | 일곱[ilgop] | 七 |

| 8 | 팔[pal] | 여덟[yeodeop] | 八 |

| 9 | 구[goo] | 아홉[ahop] | 九 |

| 10 | 십[sip] | 열[yeol] | 十 |

Actually, these ordinal numbers are not actually ordinal. They are original-Korean numbers, and used to make real ordinal numbers in some contexts. (So if you use this forms as it is, it's not an ordinal number. To know how to use them, see the end of this post.)

English-like languages have special notations for 11 and 12, but Korean-like languages doesn't have such exceptions.

| 11 | 십일 | 열하나 | 十一 | 첫 becomes 하나 if you use it after 10 or larger. |

| 12 | 십이 | 열둘 | 十二 | |

| 13 | 십삼 | 열셋 | 十三 | |

| ... (You can combine 십/열 and 1-digit numbers.) | ||||

| 20 | 이십 | 스물 | 二十 | |

| 21 | 이십일 | 스물하나 | 二十一 | |

| 30 | 삼십 | 서른 | 三十 | |

| 40 | 사십 | 마흔 | 四十 | |

| 50 | 오십 | 쉰 | 五十 | |

| 60 | 육십 | 예순 | 六十 | |

| 70 | 칠십 | 일흔 | 七十 | |

| 80 | 팔십 | 여든 | 八十 | |

| 90 | 구십 | 아흔 | 九十 | |

| 100 | 백[baek] | 百 | There is no more ordinal numbers from 100, so we use same names to cardinal numbers.2 | |

| 1000 | 천[cheon] | 千 | ||

| 1,0000 | 만[man] | 萬 | ||

| 1000,0000 | 억[eok] | 億 | ||

| 1012 | 조[jo] | 兆 | ||

| 1016 | 경[gyeong] | 京 | ||

| 0 | 영[yeong] | 零 | In middle digits of a number, we don't say anything for 0, just like English. | |

English puts a comma between every 3-digits because it uses 'thousands' scaling, but Korean puts it between every 4-digits because it uses 'ten-thousands(만)' scaling. However, 3-digits separation is more frequently used in the real life such as banks.

Some examples:

| 24 | 이십사 | 스물넷 | 二十四 |

| 101 | 백일 | 백하나 | 百一 |

| 135 | 백삼십오 | 백서른다섯 | 百三十五 |

| 2358 | 이천삼백오십팔 | 이천삼백쉰여덟 | 二千三百五十八 |

| 1,2345,6789 | 일억 이천삼백사십오만 육천칠백팔십구 | 一億 二千三百四十五萬 六千七百八十九 | |

| You may notice there is one-to-one mapping with Chinese numerals and Korean numerals. | |||

If you use 1 in places of larger than 10000, we usually add a prefix '일'(1) to the number. So 1000,0001 is 일억일, not 억일, but 1,0000 is 만, not 일만. (You may use '일만', but it's only in some formal notations.)

It's easy to think the last example as 1x108 (일x억) + 2345x104 (이천삼백사십오x만) + 6789x1 (육천칠백팔십구). If you want test yourself, there is a perl script that converts arabic numbers to Korean pronunciations. (Note that the script uses CP949 or EUC-KR encoding, not UTF-8. But I think if you copy & paste its source code in UTF-8 encoding, then it will run well in UTF-8 encoding.)

Floating numbers

To speak floating numbers, you can say '.' as 점, and the following digits in 1-digit numbers, such as:

10.13579 = 십점일삼오칠구

365.2422 = 삼백육십오점이사이이

For more mathematical notations such as equations, fractions and squares, I will introduce them (maybe far-_-) later.

Using ordinal numbers

If you use ordinal numbers as the attributive forms, the last sounds in 2, 3, 4 and 20 are dropped. The affix '-째' is something similar to '-th' in English.

| English | Korean | Desc. |

|---|---|---|

| first | 첫째, 첫번째 | '첫' is another expression of '하나' only used in ordinal numbers. |

| second | 둘째, 두번째 | you may notice that the form is varied. |

| third | 셋째, 세번째 | |

| fourth | 넷째, 네번째 | |

| fifth | 다섯째, 다섯번째 | |

| sixth | 여섯째, 여섯번째 | |

| seventh | 일곱째, 일곱번째 | |

| eighth | 여덟째, 여덟번째 | |

| ninth | 아홉째, 아홉번째 | |

| tenth | 열째, 열번째 | |

| eleventh | 열한번째 | |

| twelfth | 열두번째 | |

| thirteenth | 열셋째, 열세번째 | |

| fourteenth | 열넷째, 열네번째 | |

| ... | ... | |

| twentieth | 스무번째 | Not 스물번째 |

| ... | ... | |

| thirtieth | 서른번째 |

and so on.

You can read an article about Korean numerals on Wikipedia instead of this.

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

It has been a quite long time ago the last lecture. I've heard that some people tried reading this blog and Korean lectures, but they could not see Korean characters because their computers didn't have Korean fonts. For those, I suggest to use 'Naver Dictionary'(Windows Setup file, Linux tarball file) font.

A help page of Wikipedia will also help you.

I will continue next lectures soon. :)

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

This time, I will introduce some Korean greetings which you can use when you meet a Korean.

You should be familiar with Korean characters for more convenient reading. (Read references at the first lecture!)

You should pronunce separately each block of alphabets which are representing each Korean syllable. However, pronunciation of those alphabets is not same to English. (For exampe, 'a' is not [ei], just [a(h)].) There are also sound-linking rules for more fluent speaking, but they only make the things complicated, so I don't recommend them yet. Of course, the best way to learn pronunciation is making a Korean friend. =3=3

1. Hello / Hi / Good bye

Korean doesn't distinguish the begging greeting and the ending greeting. All we say the same thing.

Note that many words and phrases of Korean has both honorific form and friendly form. Honorific forms are used when you say to older or higher-positioned people than you. Friendly forms are used to say to your friends or younger people.

안녕하세요. [An nyeong ha se yo] : A honorific form of 'hello/hi'.

안녕. / 안녕? / 안녕! [An nyeong] : A friendly form of 'hello/hi'.

안녕히 계세요. [An nyeong hi gye se yo] : A honorific form of 'good bye'. (The friendly form of this is same to 'hello', that is, '안녕'.) But this is used only when we depart from the host.

안녕히 가세요. [An nyeong hi ga se yo] : Same to '안녕히 계세요', but only used when we are the host and the target is guest, or send off somebody.

잘 있어. [Jal It seo] : A friendly form of '안녕히 계세요.'

잘 가. [Jal ga] : A friendly form of '안녕히 가세요.'

2. See you (later/again/etc.)

또 봐요. [Tto Bwa yo] : A honorific form of 'see you'.

또 봐. [Tto Bwa] : A friendly form of 'see you'.

나중에 봐요. [Na joong e bwa yo] : A honorific form of 'see you later'.

나중에 봐. [Na joong e bwa] : A friendly form of 'see you later'.

You may notice that '~요' makes a phrase to be a honorific form. I will mention about this at later lectures on verbs.

3. Thank you

고맙습니다. [Go map seup ni da] : A honorific form of 'thank you.'

고마워. [Go ma wo] : A friendly form of 'thank you.'

감사합니다. [Gam sa hap ni da] : A 'more' honorific form of 'thank you', derived from a Chinese word '감사(感謝)'.

In fact, there are so many variations of these phrases. The reason of that will be reviewed in later lectures.

4. Good night.

Actually, most Koreans don't use different greetings such as 'good morning', 'good afternoon', 'good evening', 'good night'.

안녕히 주무세요. [An nyeong hi joo moo se yo] : A honorific form of 'good night / have a nice sleep'.

잘 자. / 잘 자라. [Jal ja / Jal ja ra] : A friendly form of 'good night / have a nice sleep'.

'안녕(安寧)' means being safe, comfortable, and not worried. This is originally a Chinese word, but became greetings of Korean at some time (I don't know exactly).

<Example>

More detailed description on grammar will be provided later.

안녕하세요? 나는 XYZ입니다. = Hello. My name is XYZ.

나[na] : I or me

는[neun] : a postposition that changes an word into a subject. (so '나는' means 'I'.)

~입니다[ip ni da] : similar to 'be' verb, in a honorific form and present tense. Basic form is '~이다'. This is not exactly a verb, actually, but an adjective verb. (details later)

벌써 밤 11시네. 잘 자라. = It's already 11pm. Good night.

벌써[bul sseo] : already

밤[bam] : night

시(時)[si] : a unit of time, one hour. This is used for pointing a particular time. To count a span of time, you should use '시간(時間)'.

~네[ne] : a far variation of '~이다', in a different style and also present tense.

'It' (the subject) is omitted at the first sentence.

선물 고마워. = Thank you for this present.

선물[seon mool] : present

There is no corresponding Korean word for 'for' in this case. (Strictly, we can think a postposition after '선물' is omitted.)

Next time, I will list some basic Korean vocabulary, only for nouns. (Verbs and adjective, adverbs should be explained after understanding verb form variations.) I think Chinese people would feel more easy because many nouns are actually from Chinese words.

* MODIFIED: respective -> honorific (commented by Dongseong Han)

- Posted

- Filed under In English/Learn Korea

NOTE: This series may have faults. If you find them, please report me by commenting.

Syntactic Features of Korean Language

Korean is very different from most European languages such as English, German, and Swedish. Theoretically, Korean is one of agglutinative languages which attach various affixes to words for grammatical purposes. This phenomena can be extensively seen in Korean verbs and nouns followed by postpositions (also known as particles).Also the syntactic structure of sentences is very different. English uses <Subject> + <Verb> + <Object> order typically, but Korean uses <Subject> + <Object> + <Verb>. Omitting the subject or objects is more frequent than English. When we decorate a noun with relative sub-sentences, English uses the order of <Target Noun> + that/which/who/whom/etc. + <Sub-sentence>, but Korean uses <Sentence ending with a verb changed into adjective form> + <Target Noun>. Korean does not exchange the subject and the verb when making questions, just changes the form of the verb. These features make many Korean people to be confused with learning (especially speaking) English-like languages because they have to think in a different order.

Korean Characters

Korean characters are very special in the point that the designer and the design philosophy are explicitly known. In the long history of Korea, there were some attempts to represent Korean sounds with simplified Chinese characters like Japan, but the final one is our current Korean characters invented by the King Sejong (세종대왕; 世宗大王), and announced in September, 1446. He named it 'Hunmin-jeong-eum (훈민정음; 訓民正音)' that means the right characters teach people widely. Despite of his effort, Korean character set was not generalized (especially for official documents) until 1894's 'Gap-oh Gaehyeok (갑오개혁; 甲午改革)'[footnote]a large renewal of Chosun's law and system conducted by the King Kojong[/footnote]. In the 1910s, a Korean researcher Sigyeong Ju (주시경) named it 'Hangul (한글)'. Actually, we had more sophisticated pronunciations and tone variations like Chinese at one time, but they were disappeared about a few hundreds years ago. You can see traces of old Korean pronunciations at 'Hunmin-jeong-eum' here, and some symbols of it are obsolete in modern simplified Hangul.Unlike Chinese characters, Korean characters represent the sounds of Korean. One character is one unit of pronunciation (called syllable or syllabe block), and each character must have at least one vowel. For example, an English word 'Carlos' which has 2 vowels is written (actually, approximated) as '카를로스' which has 4 syllables and 4 vowels, because we have to write vowels for single consonants sounds such as a sound between 'r' and 'l', and also 's'. Thus, 'Ca' -> '카[Ka]', 'rl' -> '를[Reul]', 'lo' -> '로[Ro]', 's' -> '스[Seu]'. (Note that 'r' in Korean pronunciation is not same to 'r' of English. It's something between 'r' and 'l'.)

Korean characters consist of some basic components (called 'Jamo (자모)' in Korean). Those jamos resemble the shape of our tongue when it sounds for each jamo. We combine them to make a syllable, which is the basic unit of pronunciation. If you want to know more details about jamo symbols, combining rules, and their pronunciation table, refer related articles of Wikipedia. (I think they explain better than I.)

The exact number of all combinations of modern jamos is 11,172. If you want to see the complete list of modern syllables, you may consult the Unicode 5.0 Hangul Syllables table. However, the number of most common syllables for the real life is about 3000, and also we don't memorize all syllables because we can make any sounds via combining basic jamos.

Korean computer keyboards have 2 sets of symbols for consonant jamos and vowel jamos, and are called 'Dubeolsik (두벌식)'. There is another kind of keyboard layout called 'Sebeolsik (세벌식)', which separates consonant jamos into two groups of first sound and ending sound. The printed symbols of typical Korean keyboards are dubeolsik. It is harder to learn sebeolsik because it has more keys to remember, but that layout is closer to the design principle of Hangul. You can see the keyboard layouts for various languages including Korean in this page.

The combining feature of Hangul greatly improves the input speed especially for cellphones. English cellphones usually use their own dictionaries, but Korean cellphones don't need dictionaries.

Pronunciation Features

Compared to English, Korean has less kinds of consonants and more kinds of vowels. It does not have 'z', 'v', 'w', 'f', 'r', 'th' sounds. In spite of more kinds of vowels, some of them are usually abbreviated to easier ones. These facts makes English pronunciation of some Koreans look very strange. These pronunciations were disappeared with their corresponding obsolete jamos.--

I will introduce some basic greetings in Korean at the next time. More details of syntax and vocabularies will be followed later.